TABOO MURAL INSERTS ARCHBISHOP ROMERO

INTO SALVADORAN INDEPENDENCE STRUGGLE

Some works of art are revolting because of the subject matter they depict. An ancient Roman inscription showing the Crucified Jesus with a horse’s head was so offensive to Christians that it was labeled the «graffito blasfemo». A mural commemorating the bicentennial of the Central American “Cry for Independence” unveiled in San Salvador has raised howls because it depicts Archbishop Óscar Romero alongside the man widely believed to have ordered his assassination—Roberto D’Aubuisson (click here for detail). Oddly enough, the protests have come from D’Aubuisson’s sympathizers, in a row that reveals a lot about the politics of Archbishop Romero’s image in El Salvador.

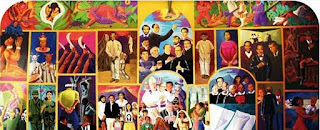

The mural, entitled “200 years of struggle for emancipation in El Salvador,” was commissioned by the Salvadoran Culture Ministry to commemorate the 200th anniversary of the movement that led to El Salvador’s independence. The mural, created by Salvadoran artist Antonio Bonilla, recalls the scale and spirit of the murals commissioned in the U.S. by the Works Progress Administration during the Great Depression—especially, the works of Diego Rivera. In the mural, Bonilla posits, as the name of his work suggests, that the independence movement was not a discrete historical event that occurred 200 years ago, but a process that has occupied El Salvador for the past two centuries, and is still underway. Thus, the mural includes scenes of El Salvador’s founding fathers ringing their liberty bell, but also includes images of a 1932 peasant uprising, of the 1989 Jesuit Massacre, and of Archbishop Romero, in a polyptych (a work of art that is divided into sections, or panels) resembling an altarpiece with contrasting motifs: pre-Columbian and colonial themes, tradition and innovation, protest and repression.

The work’s principal critic—at least, the one to publicly come forth—is the retired colonel, Sigifredo Ochoa Pérez, a man of the right. Ochoa Pérez was himself a schoolmate of Roberto D’Aubuisson, and also was accused of complicity in a wartime massacre. Although he now stands as a candidate for the national legislature for the party that D’Aubuisson founded, Ochoa Pérez traditionally was aligned with a party even further to the right, and he broke ranks with the establishment in 1989 to finger higher ups who may have ordered the Jesuit Massacre. More recently, however, he sided with the Honduran government that overthrew the democratically elected populist president. “It’s a pity, because Antonio Bonilla is an excellent artist,” Ochoa Pérez told a Salvadoran paper. “I think he betrayed his ideological preferences,” Ochoa Pérez continued. “He painted with his left hand.” But what Ochoa Pérez objected to was really not the mural’s POV, which equates leftwing uprisings to the founders. “He made a mockery of our brothers in the armed forces,” Ochoa Pérez lamented, “and also of a man who had his warts like any other leader as is Roberto D’Aubuisson, depicting him in such a grotesque way in the mural.”

For his part, Bonilla defends the depiction of D’Aubuisson alongside Archbishop Romero, as an image of reconciliation—the juxtaposition of the lion and the lamb. In fact, for Bonilla, that image was not simply an act of provocation, a grenade lobbed at museum goers. It was a carefully planned composition. A video of the mural’s creation shows Bonilla methodically painting Romero before any other figure, and using a photograph to ensure accuracy, whereas all the other figures are painted freehand, as if by painting an accurate Romero, he could inoculate himself against any other falsehood. And though the right may not like Romero’s newfound prominence, they seem to begrudgingly accept it, as when the ARENA mayor of San Salvador quieted fears that he was planning to change the name of a street named after Archbishop Romero to the name of one of the founding fathers. It turns out that Archbishop Romero has his own place within the bicentennial of El Salvador’s struggle for emancipation.

More:

Romero in Art

No comments:

Post a Comment